When it comes to navigation systems, GPS is usually the first name that comes to mind. However, the VOR navigation also holds its own in aviation circles! If you’re curious about its functions, this article is just what you need.

In this article:

What Is VOR In Aviation?

An Overview

VOR stands for VHF (Very High Frequency) Omnidirectional Range.

The main purpose is to provide airplanes with short-range navigation. Specifically, the VOR stations act as radio beacons that transmit radio signals, which aircraft with a VOR receiver can use to determine their exact position relative to the station and stay on course.

Furthermore, pilots can also use VOR in conjunction with other navigation systems. One example is the Instrument Landing System (ILS), which aids pilots during approach and landing, particularly in situations with low visibility.

Though the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) is slowly phasing out some VORs due to recent advances in technology, hundreds are still scattered across the U.S. These stations are incredible lifesavers for instrument approaches, cross-nation flights, or when pilots find themselves off track and must pinpoint the aircraft position quickly.

How Does It Work?

Step 1.

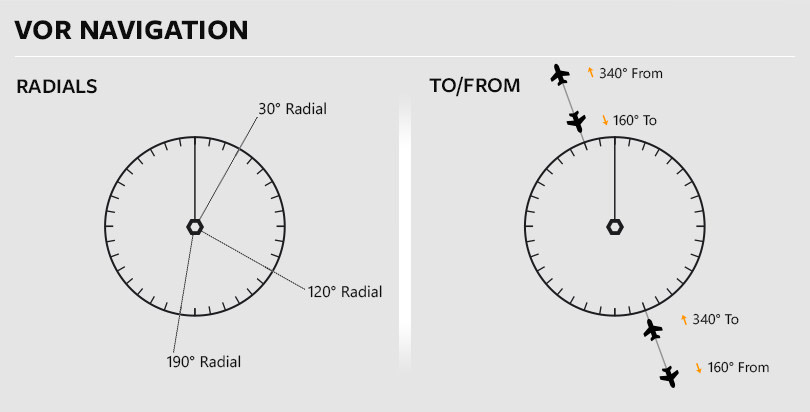

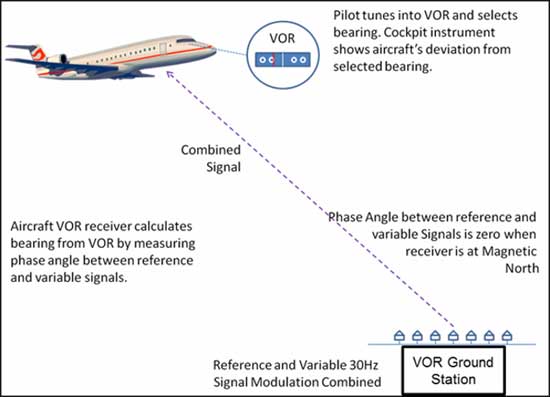

VORs operate within a frequency range of 108 to 117.95 MHz. Each VOR is aligned with magnetic north and emits 360 radial signals from the stations. It sends out a directional signal and an omnidirectional signal, known as the variable and reference phases.

Step 2.

Often mounted on the aircraft’s tail, the VOR antenna picks up these signals and relays them to the cockpit receiver. The receiver then compares the VOR’s navigation reference signal and navigation variable signal, relying on their phase difference to determine the plane’s bearing from stations (a.k.a. the radial it’s currently on).

Step 3.

Many VORs are equipped with TACAN (tactical air navigation equipment) or DME (distance measuring equipment, the most common; we will return to it later) within the station.

Those with DME clearly display readouts in the cockpit so pilots can immediately gauge their distance from the station with predictable accuracy.

Current Classifications

Back then, there were only 3 standard service volumes: High, Low, and Terminal. However, in 2020, the FAA introduced 2 new ones: VOR High (VH) and VOR Low (VL). Let’s see what they cover:

- Terminal: Extends up to 25 nautical miles (NM) from 1,000 to 12,000 feet (ft) above the plane’s receiver.

- Low: Reaches 40 NM from 1,000 ft to 18,000 ft above the plane’s transmitter.

- High: Covers 40 NM, 1000 ft (above stations) to 14,500 ft; extends 130 NM, 18,000 ft above stations to 45,000 ft; and stretches 100 NM, 45,000 ft above transmitters to 60,000 ft.

Move on to the newly added volumes:

- VL (VOR Low): Extends to 40 NM, 1,000 ft above stations to 5,000 ft; 70 NM, 5,000 to 18,000 ft.

- VH (VOR High): Consists of 5 layers from 40 to 130 NM and from 1,000 to 60,000 ft.

What Are VORs Basic Components?

As you can see in our introduction above, there are two key parts to a VOR system:

Active Antenna & VHF

Aviation aircraft are often equipped with a frequency selector (e.g., Garmin 255 GNC 255 or King/Bendix KNS 80) and a VOR antenna.

A cockpit dashboard displays important course information, such as a Horizontal Situation Indicator (HSI) or Course Deviation Indicator (CDI). Some planes also use portable VOR transceivers.

Many aircraft models, especially transport ones, have at least 2 different VOR systems installed. Most of the time, their VOR navigation service is integrated into modern decks alongside GPS; pilots can always switch between both systems!

DME (Distance Measuring Equipment)

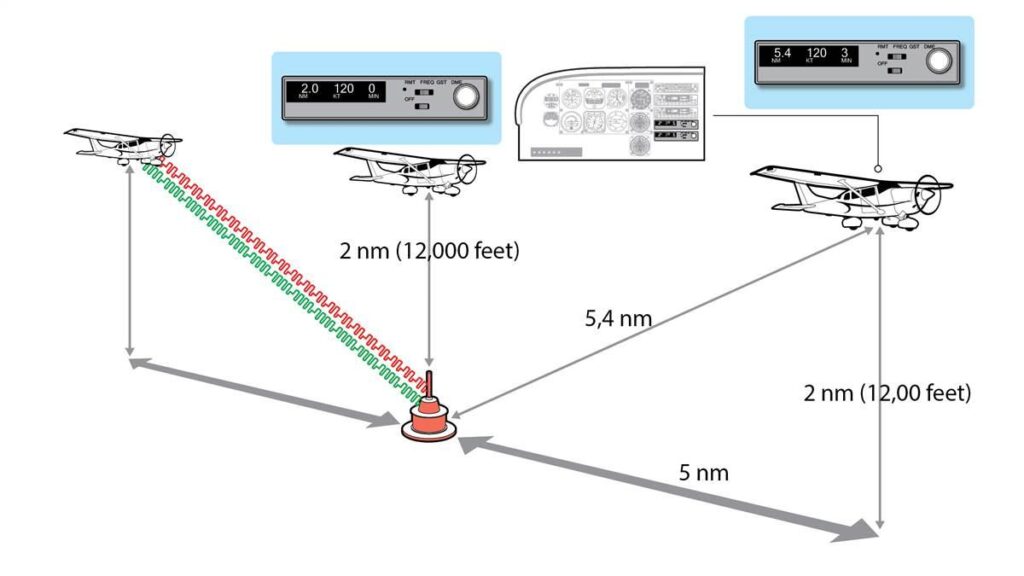

DME is often paired with large VOR stations, using UHF transponders (receiver/transmitter) on the ground and UHF interrogators (transmitter/receiver) in the airplane to measure the distance from the plane to a VOR station.

Specifically, DME measures the “slant distance,” a linear path between the receiver and the station. For instance, a plane 1 nautical mile (nm) away from the VOR station horizontally would show the same reading as a plane directly above that station 1 nm away vertically (around 6,000 feet).

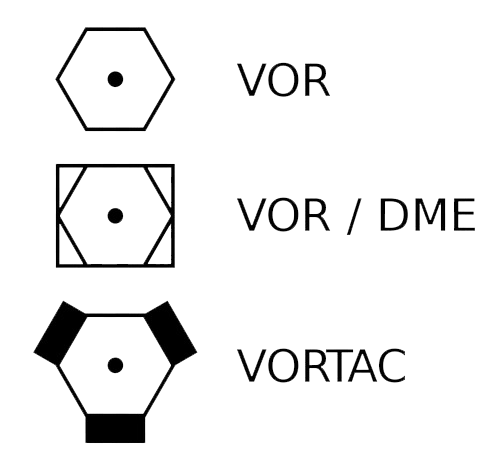

When a VOR station uses DME, it’s labeled as VOR-DME. Since VORs are being phased out, standalone DMEs sometimes appear on sectional charts as well. For example, advanced navigation systems can use the GOG (Goodsprings DME) for airlines and sometimes corporate aircraft.

VOR vs. VORTAC: Are They The Same?

Are they closely related? Yes. But are they identical? Not quite. VORTAC is a combined system with a VOR station and a TACAN (Tactical Air Navigation), another navigation system primarily used by military aircraft.

Long story short, VORTAC offers functionalities for both systems. For instance:

- Civilian aircraft can use only the VOR portion of the VORTAC to get the same navigation information as any regular VOR station.

- On the other hand, military aircraft utilize both the VOR and TACAN parts of the VORTAC for extra navigation functionalities.

To sum up, VORTAC is like a VOR with an extra feature for military aviation. So, if you are just a civilian pilot using a VOR receiver, there’s no practical difference between a VOR and a VORTAC at all.

How To Check The VOR For IFR Flights

Two common types of approach procedures if you want to ensure your VOR works for IFR flights (within 30 days):

- Option 1: Tune to a VOR Test Signal (VOT) at the airport (if available) and compare the reading to the published value (within +/- 4 degrees).

- Option 2 (for dual-VOR type): Tune both to the same VOR station, center the needles, and check the displayed bearings (difference within +/- 4 degrees).

Regardless of the method chosen, you must document the VOR check in your aircraft records, including the date, time, station used, and indicated bearing(s).

Most importantly, always consult your Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH) or other relevant guidance for specific procedures and tolerances related to VOR checks for your aircraft.

And what if your VOR check fails (the difference exceeds the +/- limits)? Then, you must rectify the issue before departure. Conducting an IFR flight despite the VOR failure will be considered illegal.

Conclusion

While VOR remains in use, we must say it’s not usually the sole navigation tool. Most aircraft come equipped with a comprehensive navigation deck offering multiple options, so pilots can always choose one that best suits the situation at hand.

Write to us if you need more aviation tutorials!