The Wright brothers’ controls evolved in a process started in 1899 with their first kite. The Wrights’ controls were the first to give the pilot full command of the aircraft. The Model “B” was the Wrights’ most popular aircraft, yet the controls are unlike anything found in airplanes today.

The Wrights’ controls of 1900-1905 were essentially the same design: the pilot lay down on the lower wing, facing the front of the aircraft. With his left hand he controlled the elevator in front, and, with a hip cradle, used his body to warp the wings. The early gliders of 1900-1901 had foot controls for the warping, and the aircraft from 1902-1905 used a hip cradle.

As with all aspects of their machines, the pilot’s position was a calculated part of their overall design. When designing the gliders, the Wrights estimated that the total drag of the glider would be one-half that of the machine with the pilot sitting upright. (Jakab, 75) Despite their success in controlled flight, their early supporter Octave Chanute expressed concern for their safety with this arrangement: “This is a magnificent showing, provided that you do not plow the ground with your noses”.

The Wrights moved to sitting in 1908, and modified the controls first for that position, then for training. The U.S. Army contract they were trying to fulfill required that the machine accommodate both a pilot and passenger. The prone position would not be a practical arrangement, and gave way to upholstered chairs mounted on the lower wing.

The F-19: Inventing the Cockpit

The Wright brothers’ controls evolved in a process started in 1899 with their first kite. The Wrights’ controls were the first to give the pilot full command of the aircraft. The Wrights’ aircraft from 1900-1905 all had the pilot operating the machine while lying on the lower wing. The controls which evolved, while practical, are far different from today’s standard aircraft controls.

All that remains of an aircraft called F-19 is the controls and a few other parts. These unique artifacts yielded invaluable information for the new set of controls, as well as a fascinating glimpse into early aviation.

The Builder: W. Starling Burgess was a yacht designer who had designed and flown a number of aircraft in collaboration with several different partners. Burgess agreed to build Wright airplanes under contract with the Wright Company, provided he paid a 20 percent royalty to the Wright Company on each airplane sold (Crouch, p. 461).

Completed in April, 1911, Burgess’ first Wright aircraft was the nineteenth aircraft he had built, which led to its designation of F-19. It was also affectionately known as “the Moth”. The aircraft was modified from the Wright Model “B”, with a reinforced, heavier airframe (Mansfield, p.17). The aircraft was sold to Charles K Hamilton, who began the aircraft’s long and varied career.

The Pilots: Charles K. Hamilton and Harry N. Atwood were two of the most colorful and celebrated pilots of their time. Hamilton in particular was known for his daring exploits. He had been a balloon, dirigible, and glider pilot, as well as the most famous stunt pilot for the Wrights’ arch rival Glenn Curtiss. He survived 63 crashes. His specialty was diving straight at the ground and pulling up at the last moment (Mansfield, p. 37). He was the first owner of the F-19, which he completely wrecked moments after his first takeoff in the machine (LeShane, p.14).

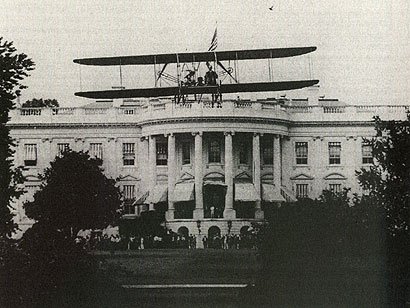

The next pilot to fly the machine was the enterprising Harry Atwood, a pilot for Burgess who had trained at the Wright school. During a record-breaking flight from Boston to Washington, Atwood crashed, and the F-19 was brought in to replace his aircraft. Hamilton accompanied Atwood on the remainder of the journey. Hamilton sold the machine to Atwood in College Park, Maryland. Atwood completed the journey by landing the machine on the White House lawn (Mansfield, pp. 37-48).

The White House Landing: On July 13, 1911, as the grand finale of his flight from Boston to Washington, Harry Atwood flew the F-19 over Washington DC, circling the Capitol, the Library of Congress, Union Station, and the Washington Monument. President Taft, who was golfing in Maryland, missed the performance.

The next day, Atwood flew back through the rain to the city from College Park, Maryland. When he was signalled that the President had finished his lunch, Atwood flew in over the South Lawn and landed, the aircraft rolling to a stop thirty feet from Taft. After a brief ceremony during which he was presented with a gold medal by the President, Atwood took off, declining his mother a ride for fear of the restricted space he had to leave the grounds.

Harry Atwood went on to greater fame as an aviator and inventor, but the F-19 was not as lucky. A week later, while on the ground, the airplane was smashed to pieces during a severe thunderstorm (Mansfield, pp. 37-48).

George A Gray: George A. Gray was a Wright trained pilot who purchased the repaired F-19 in November of 1912. Gray took the plane barnstorming throughout the East coast from 1912-15. During one performance, he met Edith “Jack” Stearns of Virginia, who later became his wife. She described flying in the F-19 in her memoir “UP”.

“As we sailed higher and faster, dipping now and then, the engine zoomed beautifully. There were no wild dips or spiral glides, but a straight-away carefully piloted flight, so smooth and uneventful that the plane seemed without a motion–a sailing magic carpet, except for a side-ways vibration as the warping of the wings met the varying air currents. We were very high up.”

Gray’s interests turned to instruction in 1915, and he demonstrated bombing and observation for the National Guard in New York and Vermont. He opened a flying school in Garden City, Long Island, where he taught for a time. In 1916, he went to Canada to open a flying school, but the plane was wrecked again, this time beyond repair.

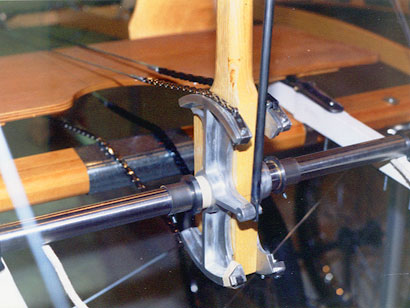

The Remains: Following George A. Gray’s failed attempt to start a flying school in Canada, the story of the F-19 is unknown until the remains of the plane were discovered in the 1960s. Purchased by the Wright Experience, the remains include the controls, the propeller shafts, sprockets, and chain guides.

The controls themselves are modified from those that were on the Wright Company Model “B” aircraft. On the standard Wright controls there were three levers: a wing warping/rudder control in the center, and an elevator control on either side. The F-19 controls, shown above, were modified from the standard Wright controls. There are four levers: two wing warping/rudder levers on each pilots’ right hand, and elevator on each pilot’s left. The student’s controls were shorter so as not to overpower the instructor.

Although different from the controls being built for the reproduction Model “B”, the F-19 controls yielded important clues about the construction and operation of the Model “B”. The instructor’s controls were made at the Wright factory, and were used by Burgess on the original plane. Thus a great many of the components were available for reproduction and for analysis in their original configuration.

Wood & Wire – Building the Model “B”

The Wright Model “B” was the world’s first production aircraft. While the methods of Wright aircraft construction have long been mysteries, the quality of the Wright Company machines has always been considered outstanding. The key seems to have been the standards set by the Wrights themselves. Grover Loening, Orville Wright’s assistant, said that Orville “directed all of the design work in the shop,” and that meticulous attention was paid to each aspect of the manufacture process (Crouch, p. 412).

The contemporary images of the factory show large, well equipped departments. Clearly the factory was not set up for assembly line production. Although it was produced in quantity by the Wright Company and other licensed manufacturers, each aircraft was assembled by hand.

The process of reproducing authentic Wright aircraft is demanding. It is always tempting to take modern shortcuts. The challenge is in meeting the exact design, materials, and standards of craftsmanship set by the Wrights themselves.

Casting Patterns

These patterns are used for the sand casting of the aluminum bell cranks which connect the control levers to the control wires.

Machining

Each crank is machined to exact specifications, based on original components.

Bell Cranks

The reproduction bell crank on the left was modeled on the original, taken from the surviving controls of Burgess-Wright F-19.

Warping Lever

This control lever was modeled on an original from the Burgess-Wright F-19. Moving the main lever forward and backward controlled the wing warping, and moving the small handle left and right controlled the rudder.

Rudder Bell Cranks

These components were duplicated using the original method of sand-casting aluminum. The cranks were both attached to the center control lever, operating both the wing warping and rudder mechanisms.

Elevator Lever

This lever controlled the elevator, and was one of two on the Model “B”. Each was installed on either side of the wing warping control. This duplicate is made from ash, with a bronze casting. Note the friction band on the base of the lever, used for keeping the control in a fixed position, allowing the pilot to let go and perform other operations, such as shutting off the motor.

Rudder Crank

The rudder is interconnected to the wing warping system. The rudder crank is attached to the warping lever but can be independently adjusted by being linked to the rudder handle atop the control lever.

Cockpit

The assembled control components of the Model “B” were arranged as shown above: the outside levers are for the elevator and moved in unison; the center column was shared between the pilot and passenger/student, and was for wing warping and rudder control. The footrest in advance of the controls is hinged at the wing to allow control assembly to be folded for aircraft shipment.

The Finished Aircraft

The assembled aircraft above is complete except for its fabric covering. All exposed wooden components also will receive an aluminum finish. The final step in the completion of the cockpit is to upholster the seats with corduroy.

The F-19: Inventing the Cockpit

The last time a Wright Model “B” flew was in 1933, when Grover Berdoll’s machine, donated to the Franklin Institute, made a short hop in Camden, New Jersey. While an authentic flying Model “B” is in production at the Wright Experience, we can learn much about flying the machine itself from early aviators, our custom flight simulator, and even our radio-controlled model. The Wright Model “B” was used for instruction at schools including the Wrights’, the US Army’s, and others established by former Wright pilots.

The Wrights established their flying school in 1910. Their first student was Walter Brookins. The school was first operated in Montgomery, Alabama, and was later moved to the Wrights’ home field of Huffman Prarie outside Dayton, Ohio. The field was also known as Simms Station.

Orville was the original instructor at the school, and managed other instructors as they became qualified. Orville set the standards by which the student pilots were trained. There was considerable emphasis placed on maintenance of the machines. Each pilot became fluent in the mechanics and repair of the Wright aircraft. Students practiced flying in a machine known as the “balance” machine, which was an older Wright plane set up on the ground with functioning controls, something like a modern flight simulator.

Students were taught to fully control their machines and how to handle emergency situations, such as having the engine quit. Orville instructed many of the students personally, preparing them for their appearances as members of the Wright demonstration team.

Students typically learned to fly in under eight hours of instruction. Many of the graduates of the Wright school were the most famous aviators of their time: Arch Hoxsey, ‘Cal’ Rodgers, Ralph Johnstone, Frank Coffyn. Henry “Hap” Arnold went on to establish the United States Air Force (Crouch pp. 426-428, 435-439).

The Stinson family of San Antonio, Texas holds a unique position in the history of American aviation. In 1912, at the age of 21, Katherine Stinson was the first of her four siblings to learn to fly . In 1914, her younger sister Marjorie learned to fly on Model a “B” at the Wright school in Dayton, Ohio. Marjorie became known as “The Flying Schoolmarm” for her instruction of over 80 Canadian pilots during World War I (Weingarten, p. 31-34).

During her days at the Wright school, Marjorie kept a diary, which was published in Aero Digest magazine in 1928. The diary gives a glimpse of the life of a Wright student. Marjorie seems particularly interested in being free of her instructor, Howard Rinehart.

July 10: A.M. One flight, 3 min. P.M. One flight 3 min. We cut them short to get more landings. I think that if I could persuade this man Rinehart to get out of the plane, I could fly it and land it myself. I might try telling him that a lady likes to see him walking about the field.

July 22: A.M. Two flights, 4 min. P.M. One flight 3, min. Rinehart doesn’t say much to me. I do believe I am doing all the flying myself, but could only be sure if he stayed on the ground. He just sits in the plane with hands folded. Told me he was going to give me a surprise landing by cutting the motor on me so I am not supposed to look at him, but to land quickly when the motor quits.

Juy 24: A.M. Rinehart is smart. I have a weakness for looking at a tall cornfield, and just as we were over it, he cut the motor. With the grace of what little altitude I had and his presence (if not his help) I got back to the field without any breakage.<

August 4: Something broken. No flying. P.M. Fixed again, one flight with Rinehart and one 2 min. flight alone, also one set of figures eight alone. It was great to look over and not see Rinehart beside me. I knew exactly who was flying then, and I could almost hear the other students’ sigh of releif when I stepped out of the plane leaving it all in one piece, that they might later fly in it. (Stinson, Aero Digest p. 169)

Katherine and Marjorie’s younger brothers Jack and Eddie also became pilots. The family business, Stinson Aviation, became one of the most respected companies in the industry.

Frank Coffyn was taught to fly at the Wright school in Dayton in 1911. An article published in Collier’s Magazine in September 1911 gives an account by one of Coffyn’s passengers, Richard Harding Davis.

I crawled between a crisscross of wires to a seat as small as a racing saddle, and with my right hand choked the life out of a wooden upright. Unless I clung to Coffyn’s right arm, there was nothing I could hold on to with my left but the edge of the racing saddle.

My toes rested on a thin steel cross-bar. It was like balancing in a child’s swing hung up from a tree. Had I placed myself in such a seat on a hotel porch, I would have considered my position most unsafe; to occupy such a seat a thousand feet in mid-air while moving at fifty miles an hour struck me as ridiculous. “What’s to keep me from falling out?” I demanded. Coffyn laughed unfeelingly. “You won’t fall out!” he said.

I began to hate Coffyn and the Wright brothers. I began to regret I had not been brought up a family man so that, like the other men of family at Aiken, I could explain I could not go aloft, because I had children to support. I was willing to support any number of children. Anybody’s children. I regretted too late that, except for a paltry mug or two, even to my godchildren, I had not done my duty. I wanted to get down at once, and hear my godchildren say their catechism.

Behind us the propeller was thrashing the air like a mowing machine, and Coffyn had disguised himself in his goggles. To me the act suggested only the judge putting on his black cap before he delivers the death sentence. The moment had come. I tried to smile at my two faithful friends, but one was excitedly dancing around taking a farewell snapshot, and the other already was calmly counting my money.

On the bicycle wheels we ran swiftly forward across the polo field. There was no swaying, no vibration, no jar. We might have been speeding over asphalt in a soft-cushioned automobile. We reached the boundary of the polo field.

“You are in the air!” said Coffyn. I did not believe him, and I looked down to see, and found the earth was two feet below us. We were moving through space on as even a keel as though we still were touching the level turf.

And then a wonderful thing happened. The polo field and then the high board fence around it, and a tangle of telegraph wires, and the tops of the highest pine trees suddenly sank beneath us. We seemed to stand quite still while they dropped and tumbled. They fell so swiftly that in a moment the Whisky Road became a yellow ribbon, and the Iselin house and gardens a white ball on a green billiard cloth. We wheeled evenly in a sharp curve, and beyond us for miles saw the cotton fields like a great chessboard. Houses and barns and clumps of trees were chess men.

Coffyn tried to tell me something of, I believe, a reassuring nature; but the thrashing of the engines and the steady roar of the propellers drowned his voice. I did not particularly care to hear. Already I had confidence in Coffyn that no assurance of his could strengthen, and I had got into another world, one which to him, through long association was no longer a miracle.

Charles Wald was instructed at the Wright school in 1912. He was instructed by A.L. Welsh and went on to run a ‘hydroaeroplane’ school in Long Island in 1912. Like Marjorie Stinson, he left behind a log book of his instruction days, suggesting the constant maintenance required for the Model “B”.

June 29: Replaced broken roller in chain.

July 2: Stay wire of horizontal rudder broken at eyelet.

July 3: Lost pin holding exhaust rocker arm causing missing cylinder.

July 4: Skid broken by rough landing in hummocks, break showed skid partly rotted. New skid fitted in two hours.

July 6: Rear truss wire at skid broke at loop in leaving ground breaking rib and nicking propeller.

July 8: Propeller broken by running machine into shed under power, machine running off run way and striking floor. Replaced with spare propeller.

July 16: …replaced broken roller in chain.

July 20: Connecting rod #2 cylinder broke at bronze casting below wrist-pin bearing, breaking entire piston and cam shoes, the obstruction jamming in crank case, tearing hole in crank case… Altitude at time about 300 ft.

(Wald, pp. 66-67)

Flying the Simulator: In 2001, Birhle Research Inc, Old Dominion University, and the Wright Experience worked together to produce a flight simulator of the Model “B”. The simulator includes Birhle’s PC simulation environment, D-Six, a full scale Model “B” cockpit, and a projected image in front of the pilot.

The computer model of the aircraft was produced from a set of drawings. Using a computational aerodynamics program, a computer predicted the model’s forces and moments. The D-six program integrates this data into the aircraft equations of motion to simulate flight. When the full scale aircraft is completed and tested in the wind tunnel, the tunnel data will replace the predicted data.

The display in front of the pilot is generated by a second graphics computer, which is in communication with D-Six. The wooden controls have been specially adapted to the simulator program.

Flying the R/C Model: The R/C model showed our team the three axes of control of the Model “B”:

- Roll: The wingtips warp, the aircraft banks left and right

- Pitch: The elevator warps up and down, the aircraft climbs and levels off

- Yaw: The rudder pivots right and left, the aircraft turns left and right

The model was constructed in 1999, based on drawings and on the Model “B” originally owned by Grover Bergdoll, now in the collection of the Franklin Institute.

Flying the New Model “B”: A flyable 1911 Wright Model “B”, is currently in production and will be featured in a PBS NOVA film “Inventing the Flying Machine”. It will be identical to two static aircraft built for the Fort Rucker and College Park aviation museums. The only difference is that they do not have operating engines. Our flying model B will be powered by an original Wright engine, Vertical Four Serial #20!

Upon completion, the aircraft will be thoroughly tested in a wind tunnel to gain flying experience and accurate data for the simulator. Flight testing will begin after the wind tunnel tests.