The Wrights didn’t always work alone. When it came to the 1903 Flyer, they relied on their friends and neighbors of Kitty Hawk. In previous years they greatly depended on the local population, particularly the Tate family. The gliders required only one other person to help the Wrights in flight tests. The Flyer was a different story. It was much heavier, and required several willing souls to help cart it to and from the launch rail.

The men of the U.S. Lifesaving Service stationed near Kitty Hawk proved invaluable to the Wrights in the trials of the 1903 Flyer. They assisted Orville and Wilbur with each test of the Flyer. Perhaps their most significant contribution to the Wrights was simply their presence: they were the crucial witnesses to the first flights.

The 1903 Flyer we know today is not exactly the machine that flew at Kitty Hawk. The story of the machine hanging in the Smithsonian is one of both the brilliant engineering of the Wrights as well as all the confusion and controversy of their achievement. Unlike most Wright experimental machines, the 1903 Flyer was salvaged and returned to Dayton, beginning a long journey of neglect, flood, exile, and, finally, a return to honor.

The Flyer never had it easy—its construction was beset with problems, and its flying career lasted all of five flights. The construction of the 1903 Flyer was a move into uncharted territory for the Wrights. They had little experience with engines, and none with propellers. Success was far from guaranteed. The design of the 1903 Flyer was a confident extension of the 1902 glider. Its assembly in Kitty Hawk was a frustrating trial. Its success in December 1903 was both monumental and momentary.

The design of the 1903 Flyer was essentially an extension of their 1902 glider, accommodating the weight and size of the engine, chain transmission, and propellers. The Flyer is unique among the Wrights’ early aircraft in that a preliminary drawing for the machine actually exists and belongs to the collection of the Franklin Institute.

The Flyer was actually constructed in two stages—in Dayton and in Kitty Hawk. All the components were fabricated in Dayton, including the engine and propellers. The building of the engine marked the first real collaboration with someone else on one of their machines. The mechanic from their bicycle shop, Charley Taylor, did almost all of the construction of the engine, building it in a remarkably short six weeks.

The completion of the machine in Kitty Hawk was anything but easy. Although the airplane’s parts arrived intact after the long journey to the Outer Banks, and the initial assembly went smoothly, once tests began, the Wrights had trouble with the engine and with the propeller shafts, which cracked twice. Each time a new set had to be remanufactured in Dayton. The second set required Orville to return, leaving Wilbur alone in the encroaching winter.

Once the troublesome propeller shafts had been replaced, the machine was given a thorough set of tests to determine that it could perform according to all the design and calculation work done in Dayton. The engine and propellers were determined to be producing adequate thrust in order to power the aircraft. Flight tests could actually begin.

The first flight test was made on December 14, 1903, with Wilbur as pilot. He left the track quickly, and the machine pitched up steeply, lost speed, and came to the ground after only a few seconds in the air. The brothers did not consider it a success. The machine was damaged, delaying the next trials until after the repairs could be made.

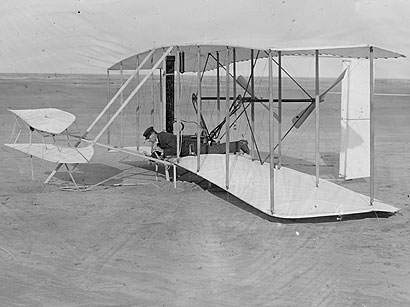

The famous flights of December 17th, 1903 completed the flying career of the Flyer. Orville’s brief success was followed by two flights of similar but increasing length with the brothers alternating as pilot. The fourth and final flight might be rightly regarded as the definitive proof that the Flyer was the world’s first airplane, flying 852 feet in 59 seconds.

The aftermath of that last flight is shown above. Wilbur landed hard, breaking the entire canard assembly off the front of the machine. After the machine was carried back to the shed, it was overturned by a gust and destroyed. The parts were carried into the hangar, and the Flyer never left the ground as an airplane again.

The machine sat crated in a shed for 13 years. Its years of neglect ended with exhibitions which gave way to a 25-year exile in England. The Flyer’s return to Dayton was less than heroic and it was met with both veneration and controversy. Although salvaged and stored in their backyard shed, it was virtually forgotten by the Wrights. Only long after their worldwide success did the Flyer re-emerge.

Following its destruction in 1903, the Flyer remained in its crates in a shed on the Wrights’ property, all but forgotten. Ten years after its first disaster, it met a second. The flood of 1913 was one of the worst in Dayton’s history, killing hundreds and destroying large portions of the town. The crates holding the Flyer were completely submerged. When Orville opened the crates, it was discovered that the thick layer of mud covering the crates had actually preserved the Flyer. All the Wrights’ early documents, diaries, and photographic negatives of their early experiments had also survived. (Crouch, p. 453-454)

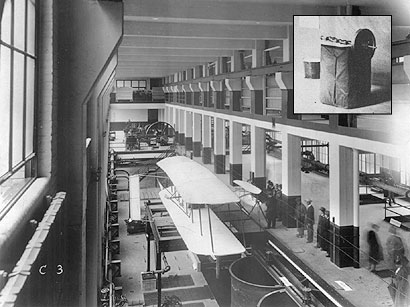

The first time any part of the Flyer was exhibited was in 1906 at the first aeronautical exhibition in New York City—the flywheel and crankshaft were placed on display on a pedestal (see inset). After the exhibition, they disappeared, and have never been found.

At the request of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Orville reconstructed the Flyer for the first time since 1903. According to the exhibit label, “the front and rear rudders had to be almost entirely rebuilt. The cloth and the main cross spars of the upper and lower sections of the wings also had to be made new. A number of other parts had to be repaired, but most of the other parts, excepting the motor, are the original parts used in 1903.” It was only on display for two days in June, 1916.

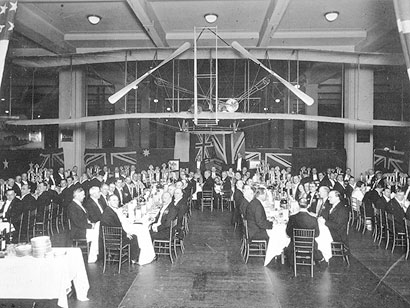

The exhibition was followed by the Flyer being shown at the Pan-American Aeronautical Exhibition in 1917, and then in Dayton between 1918 and 1925, beginning its long life as an object of curiosity and admiration (Crouch, p.492).

The Wrights patented the control system of their 1902 glider in 1906. The authorship and use of this system was at the heart of the many lawsuits they brought against their competitors, and these pictures were made as evidence for one of the trials (Crouch, p. 497). The 1903 Flyer was the earliest surviving machine to use the system, having the same system as the destroyed 1902 glider.

From 1928 until 1948, the Flyer was on display at the Science Museum, London. Orville sent it out of the country to protest the Smithsonian Institution’s claim that Samuel Pierpont Langley’s “Grand Aerodrome” of 1903 was the first machine capable of powered flight. The Wrights had relied on the Smithsonian at the outset of their work in 1899. Now the Institution was seen by Orville to be committing a serious act of fraud.

The controversy was complex. In the course of the lawsuits between the Wrights and Glenn Curtiss, successful flight tests had been carried out by Curtiss on a reconstruction of the Aerodrome. These tests were meant to show that the Wright’s early rival had been capable of powered flight before the Wrights. Orville objected to the tests, because significant modifications had been made to the old Aerodrome to make it airworthy. The Smithsonian accepted a report claiming the authenticity of the tests, and labeled the Aerodrome the first machine “capable” of powered flight.

As long as the Smithsonian maintained the word “capable” in its text about the Aerodrome, Orville would not give the Flyer to the museum, and sent it to England where there was no such question. Only after decades of effort and negotiation by countless people, including the likes of Charles Lindbergh, did the Smithsonian recant to Orville’s satisfaction.

It was a bitter and ironic dispute. The Wrights had relied on the Smithsonian at the outset of their experiments, and had always held Langley and Charles Manly (Langley’s engineer and pilot) in high regard. They had been awarded the Smithsonian medal. The dispute put all of this aside (McFarland, p. 1169).

Orville Wright ended the Flyer’s exile in 1943, but did not live to see its return. The Smithsonian has since become a great repository of Wright aircraft, with three original machines, engines, documents, and a renowned tradition of scholarship and care for the Wright legacy. In his agreement with the Smithsonian, Orville gave the Flyer its final home: the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. When it returned in 1948, it finally received a triumphant homecoming. The Flyer’s return to the U.S. helped settle an old score, and secure a pe

Thanks to the National Air and Space Museum, the Flyer has come to rest and is proudly restored and on display in Washington DC. Their painstaking conservation and preservation of the machine allows us to see “inside” the Wrights’ most famous airplane. The National Air and Space Museum truly gave the Flyer its most scientific and meticulous conservation ever.